Italiano

Listen

to

Saverio Selecchy's

"Miserere"

Orchestra e Coro

dell'Arciconfraternita

del Sacro Monte

dei Morti

di Chieti

Download

Real Audio

Player

|

|

.

MISERERE

Holy week

traditions

Text by

Emiliano Giancristofaro |

Many

of Abruzzo’s profoundly felt Holy Week religious rituals have survived thanks to popular tradition that has

also enhanced them with a number of customs and ceremonies. In fact, there are numerous

credences, prayers and popular litanies, processions and religious plays (that have

recently undergone an singular revival thanks to the interest of the young), popular rites

that can be seen during Easter week, especially amongst elderly people or in rural and

mountain communities. In all of this we can often read an interest for folklore and a

familiarity with popular cultural heritage, but we also have living evidence that is

vastly important for sociologists and anthropologists because it exposes extraordinary

expressions of popular religiousness as opposed to forms of "official" religion.

One of the sacred rituals most deeply felt by the Abruzzese is that of Good survived thanks to popular tradition that has

also enhanced them with a number of customs and ceremonies. In fact, there are numerous

credences, prayers and popular litanies, processions and religious plays (that have

recently undergone an singular revival thanks to the interest of the young), popular rites

that can be seen during Easter week, especially amongst elderly people or in rural and

mountain communities. In all of this we can often read an interest for folklore and a

familiarity with popular cultural heritage, but we also have living evidence that is

vastly important for sociologists and anthropologists because it exposes extraordinary

expressions of popular religiousness as opposed to forms of "official" religion.

One of the sacred rituals most deeply felt by the Abruzzese is that of Good  Friday, celebrated everywhere with great

solemnity and heartfelt participation; it is the anniversary of a sorrowful day, of

mourning for the entire Catholic world and this explains why it gives rise to so many

credences across the region. There are still women who do not sweep the house that day, no

tablecloth is spread, and there are still those who fast for the entire time the bells are

bound. Widespread superstition exists regarding what is about to happen, that is to say

Christ’s resurrection and the unleashing of the bells, a theme recurring as a healing

element in many adjurations (a famous incantation is: Holy Monday, Holy Tuesday, etc,

Sunday is Easter Day and all the worms fall to the ground!). The most solemn Good Friday

ritual is undoubtedly the procession of the Dead Christ which in many towns reveals

ancient ties with medieval sacred theatre, as in the churchyard performances by religious

fraternities. From a folkloristic aspect the most interesting processions are: Chieti,

L’Aquila, Friday, celebrated everywhere with great

solemnity and heartfelt participation; it is the anniversary of a sorrowful day, of

mourning for the entire Catholic world and this explains why it gives rise to so many

credences across the region. There are still women who do not sweep the house that day, no

tablecloth is spread, and there are still those who fast for the entire time the bells are

bound. Widespread superstition exists regarding what is about to happen, that is to say

Christ’s resurrection and the unleashing of the bells, a theme recurring as a healing

element in many adjurations (a famous incantation is: Holy Monday, Holy Tuesday, etc,

Sunday is Easter Day and all the worms fall to the ground!). The most solemn Good Friday

ritual is undoubtedly the procession of the Dead Christ which in many towns reveals

ancient ties with medieval sacred theatre, as in the churchyard performances by religious

fraternities. From a folkloristic aspect the most interesting processions are: Chieti,

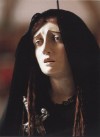

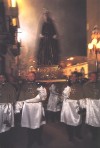

L’Aquila, Sulmona, Lanciano, Vasto and Teramo, and many, many more in a minor key. The Dead Christ

(often a wooden statue by unknown artists of centuries past: it is said that the Lanciano

Christ was sculpted by a Poor Clare nun who went mad as soon as it was finished) is

preceded by all the symbols of the Passion: the lantern, the cockerel that crowed at St

Peter’s denial, the whipping post and cords, the crown of thorns, the ladder, the

hammer, the pincers, the sponge soaked in vinegar, the lance, St Veronica and the veil (in

Teramo, for example, this is carried by four women dressed in mourning, whilst the

troccolante keeps time with the hoarse rattle of the wooden clapper) otherwise a brass

band plays woeful, solemn funeral marches by local composers such as Masciangelo

(Lanciano) and Selecchi (Chieti). Next in the processions come the fraternities of the

Dead Christ, still numerous in Abruzzo, with the women dressed in mourning reminiscent of

the ancient companies of the Disciplined, then

Sulmona, Lanciano, Vasto and Teramo, and many, many more in a minor key. The Dead Christ

(often a wooden statue by unknown artists of centuries past: it is said that the Lanciano

Christ was sculpted by a Poor Clare nun who went mad as soon as it was finished) is

preceded by all the symbols of the Passion: the lantern, the cockerel that crowed at St

Peter’s denial, the whipping post and cords, the crown of thorns, the ladder, the

hammer, the pincers, the sponge soaked in vinegar, the lance, St Veronica and the veil (in

Teramo, for example, this is carried by four women dressed in mourning, whilst the

troccolante keeps time with the hoarse rattle of the wooden clapper) otherwise a brass

band plays woeful, solemn funeral marches by local composers such as Masciangelo

(Lanciano) and Selecchi (Chieti). Next in the processions come the fraternities of the

Dead Christ, still numerous in Abruzzo, with the women dressed in mourning reminiscent of

the ancient companies of the Disciplined, then  there

is Christ’s bier, often carried shoulder high, traditionally by certain categories of

citizens. In Bomba the Madonna in mourning was carried by four girls in black; at

Castiglione Messer Marino, Gamberale, Montenerodomo, after the procession Christ was laid

in the sepulchre and vigil kept through the night, mostly by womenfolk who took turns to

stay in the sepulchre so that"Jesus is not alone", a tradition in all Abruzzo

funerals. Almost every Abruzzese town has a Calvary, with three crosses, that becomes the

destination of many pilgrimages around Holy Week. The Good Friday processions in Abruzzo

are really of Spanish origin and taste, especially in the manner of depicting mourning and

sorrow for the death of Christ, with grief manifested just as it is in funeral traditions

all over Southern Italy. In some processions, however, elements of medieval performances

survive, for instance that of the tamurro, the drummer, a hooded figure that beats time on

a drum, or the Cyrenian, who drags a heavy cross and stumbles three times to remember how

often Jesus fell. Many years ago it was far more common to see sacred performances of the there

is Christ’s bier, often carried shoulder high, traditionally by certain categories of

citizens. In Bomba the Madonna in mourning was carried by four girls in black; at

Castiglione Messer Marino, Gamberale, Montenerodomo, after the procession Christ was laid

in the sepulchre and vigil kept through the night, mostly by womenfolk who took turns to

stay in the sepulchre so that"Jesus is not alone", a tradition in all Abruzzo

funerals. Almost every Abruzzese town has a Calvary, with three crosses, that becomes the

destination of many pilgrimages around Holy Week. The Good Friday processions in Abruzzo

are really of Spanish origin and taste, especially in the manner of depicting mourning and

sorrow for the death of Christ, with grief manifested just as it is in funeral traditions

all over Southern Italy. In some processions, however, elements of medieval performances

survive, for instance that of the tamurro, the drummer, a hooded figure that beats time on

a drum, or the Cyrenian, who drags a heavy cross and stumbles three times to remember how

often Jesus fell. Many years ago it was far more common to see sacred performances of the crucifixion through which the population

relived the Passion with great emotion. Gennaro Finamore tells of Capistrello, near

L’Aquila, where on Good Friday morning a man dressed as a Roman soldier arrived on a

white horse and rode through the town searching for Jesus, calling him loudly. Then, one

by one, others dressed as soldiers joined in the search until Jesus, played by a young

man, was found. In the town square, before a crowd of people, the priests, Herod, Pilate,

he was insulted and slapped, then crowned with thorns and given a heavy cross to carry as

far as the Calvary Church where he remained until Holy Saturday when he was unbound: in

acting the scene of the Resurrection the soldiers on guard were sometimes so realistic

that they hurt themselves. Religious performance and popular religious theatre are part of

an old "Southern craft", and it is no surprise to find that recently there has

been a revival of these sacred happenings, especially amongst the young; the Passion of

Christ is performed in many towns in Abruzzo, using new techniques and themes that often

indicate that traditional religious themes and sacred legends have been mixed with painful

and tragic crucifixion through which the population

relived the Passion with great emotion. Gennaro Finamore tells of Capistrello, near

L’Aquila, where on Good Friday morning a man dressed as a Roman soldier arrived on a

white horse and rode through the town searching for Jesus, calling him loudly. Then, one

by one, others dressed as soldiers joined in the search until Jesus, played by a young

man, was found. In the town square, before a crowd of people, the priests, Herod, Pilate,

he was insulted and slapped, then crowned with thorns and given a heavy cross to carry as

far as the Calvary Church where he remained until Holy Saturday when he was unbound: in

acting the scene of the Resurrection the soldiers on guard were sometimes so realistic

that they hurt themselves. Religious performance and popular religious theatre are part of

an old "Southern craft", and it is no surprise to find that recently there has

been a revival of these sacred happenings, especially amongst the young; the Passion of

Christ is performed in many towns in Abruzzo, using new techniques and themes that often

indicate that traditional religious themes and sacred legends have been mixed with painful

and tragic  aspects

of contemporary life such as emigration, unemployment, violence and poverty. The evidence

points to the desire for a recovery of authentic Christian values and the rejection of the

absurdities of modern society. In this light ancient ballads inspired by sacred legends

preserved in the vocal tradition and the lauds born in Medieval religious fraternities

have regained popularity; in fact, Toschi still maintains that the spoken laud was

probably the first form of sacred drama, recited in churchyards during major religious

feastdays. From this root the Passion ballad emerged and during Holy Week this used to be

repeated from one village to the next by popular story-tellers in memory of the torments

and martyrdom of Jesus Christ. aspects

of contemporary life such as emigration, unemployment, violence and poverty. The evidence

points to the desire for a recovery of authentic Christian values and the rejection of the

absurdities of modern society. In this light ancient ballads inspired by sacred legends

preserved in the vocal tradition and the lauds born in Medieval religious fraternities

have regained popularity; in fact, Toschi still maintains that the spoken laud was

probably the first form of sacred drama, recited in churchyards during major religious

feastdays. From this root the Passion ballad emerged and during Holy Week this used to be

repeated from one village to the next by popular story-tellers in memory of the torments

and martyrdom of Jesus Christ. |